David Grann's meticulous, riveting book Killers of the Flower Moon is not, in itself, an angry or vengeful piece of writing, but the feelings it evokes in a reader are ones of anger and vengeance. Reading it is a harrowing experience, one that opens the vein of the past to find the blood inside has been poisoned with racism, bigotry, intolerance and hate, all cloaked by the veil of the American flag. The story it tells is both largely unknown and genuinely unforgettable.

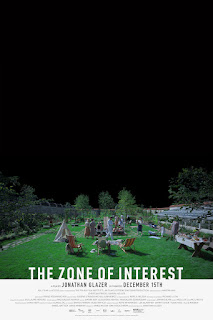

Now, Martin Scorsese has made a $200-million dramatic adaptation of Killers of the Flower Moon, and it is a grand and thudding disappointment, dramatically wrong-headed, apparently lacking in any self-awareness that the story it tells is not at all the story that matters.

The story told in the book is an epic, sweeping one, spanning many decades, beginning with the U.S.-sanctioned ethnic cleansing and forced diaspora of millions of native Americans, commonly called the "Trail of Tears," and leading to a series of shocking murders (and they truly are shocking), many of which involve family members of a woman named Molly Burkhart.

Molly and her family are Osage "Indians," native Americans who were herded to a rocky, ugly part of the Oklahoma prairie, where the American government figured they would lead hardscrabble lives, if they led any lives at all. Someone forgot to check the ground, because it turns out that Osage land was some of the richest in oil anywhere in the United States. Within years, the Osage people became the richest Americans, and some of the richest people anywhere in the world. Then they began to die.

Molly Burkhart's sister was one of the first recognized murders. Her story is one of pain and anguish, as Molly watches the destruction of her land, her home, her community, her people, her family, and ultimately her marriage and, almost, herself.

There's a key plot point in the book that normally would be considered a spoiler, if the film's trailer didn't give it away so clearly: the perpetrators of some of these horrific murders are Molly's seemingly loving husband and his uncle, a pillar of the community and supporter of Osage rights. Except he's not. He's doing it all for the money.

And this is what the movie version of Killers of the Flower Moon gets so wildly wrong: It turns a story about one person, one family, one community, and one people who are degraded and devalued and dehumanized every single day, and who fight so hard to have these murders solved, and turns it into a Martin Scorsese gangster melodrama.

The most brutally inhuman people in the story, William Hale (Robert De Niro) and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), Molly's husband, are made into its stars. A roster of white men cycle in and out of Killers of the Flower Moon, some of them dastardly villains, some noble heroes, and by and large this is their movie, this is their story. That it takes place on Osage land is mostly not germane to the story. Scorsese and screenwriter Eric Roth, both of whom should know better than this, let the movie become a story about white men ratting out other white men. About one white law enforcement officer going toe-to-toe with white crooks.

Throughout, once in a while we get to see more of Molly herself (Lily Gladstone), mostly as she suffers in incoherent pain while her husband administers poisoned insulin to try to kill her.

The purpose of all these deaths is "head rights," the legal process that ensures the relatives of a dead Osage who owned rights to oil and mining deposits, would automatically pass them to the next of kin. To make sure head rights went to the "right kind" of people (that is, Whites), greedy, unscrupulous White men started marrying Osage women, then systematically poisoning them or arranging their deaths in myriad ways. They'd even kill the children, too, if that's what it took.

Grann's book details all this in astonishing clarity. Scorsese can never quite latch o to the story, because to do so requires the entire movie be told from the perspective of the Osage, particularly the Osage women, particularly one Osage woman—Molly Burkhart. That's not what the movie wants to give us.

I've rarely seen a movie so utterly unable to hone in on its story. Even at 3 hours, 26 minutes, Killers of the Flower Moon seems to have left too much on the cutting-room floor. Relationships aren't clear, consequences aren't clear, motives aren't clear. You can watch the film and get a good idea of what's happening, but it takes a little bit of effort.

The true story of what happened to the Osage—not just to the Burkhart family, not just to this small community, but to thousands, maybe even more, of Osage over the years—deserves to be told. Alas, Killers of the Flower Moon hasn't nailed it, despite the glowing, magnificent performance of Lily Gladstone as Molly, who should be the biggest star in the movie, but is third billed.

Killers of the Flower Moon isn't a bad movie. Elements of it are remarkable, particularly a jaw-dropping set design. Gladstone commands the screen every time she's on it, though De Niro still mugs too much, and Di Caprio seems slightly out of his depth here in a nuanced, complicated role. He's put in the unenviable position of having the audience knowing his terrible deeds, even as they watch him coming home and making love to Molly. He is the bad guy, but the movie wants to position him as the romantic lead. Hitchcock might have been able to get away with that; Scorsese and screenwriter Eric Roth are incapable. Grann conceals the truth about the nature of these men until midway through, but the film sets them up as the bad guys—Scorsese's beloved gangsters—from their first scene.

For a director whose first mainstream success was the female-focused Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, it's confounding that he struggles to put Molly—not Ernest and Hale—at the center of this story. Sure, DiCaprio is the bigger star, but Gladstone displays her character's soul, one wracked by terrible feelings of hatred, death, and loss. By all rights, she's the star of the film and Molly should be the star of the story (in this streamlined version, at least), and Killers of the Flower Moon would have been infinitely better if it had let her be exactly that.

As a finale, the movie has a group of elite white radio actors tell the rest of the story, segueing to a group of nameless, faceless Osage performing a ceremonial dance, Killers of the Flower Moon highlights exactly what it gets so disastrously wrong: showing the White people in close up, giving them names and personalities, while dismissing the Osage as anonymous pawns.

It's enough to get admirers of the book angry all over again.

Viewed Friday, Oct. 21 — AMC Universal 12

1745